Microsoft’s recent decision to absorb higher electricity costs and replenish water use for new data centers did not focus on AI performance or cloud capability. It addressed a more fundamental issue: whether communities are still prepared to host AI infrastructure.

In its official sustainability announcement, Microsoft acknowledged rising resistance and the need to change how data centers are introduced.

I think the bare minimum, as we look to the future, is to give these communities around the country the confidence that when a data center comes, its presence will not raise their electricity prices.

Microsoft President, Brad Smith CNN

That statement marks a shift. AI expansion is now colliding with physical limits on electricity supply, water availability, and grid stability. These limits are no longer abstract. They are appearing as delayed interconnections, contested water permits, and canceled projects.

The physical footprint of AI is now a local issue.

LCA Puts Evidence in the Room Before the Excavators Arrive

AI infrastructure is still often described as virtual. In practice, data centers are among the most resource-intensive assets being deployed.

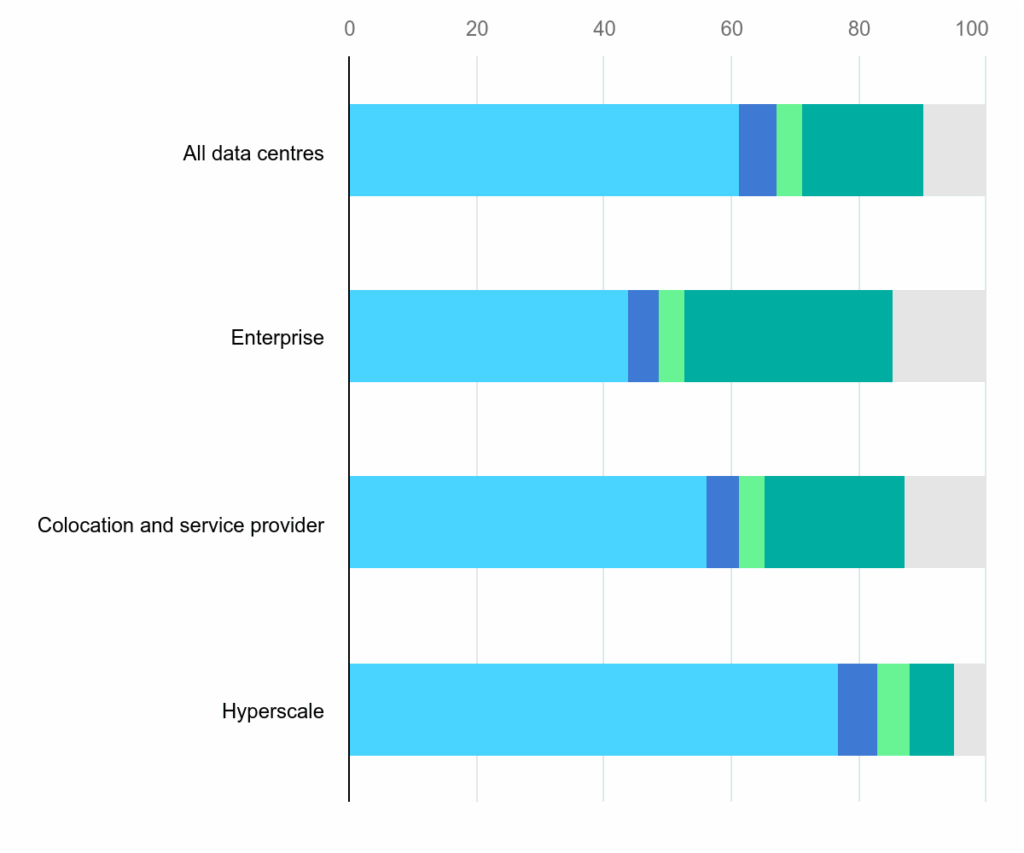

The International Energy Agency estimates that global data center electricity demand reached about 460 TWh in 2022 and is expected to more than double by 2026, mainly due to AI workloads.

In the United States, data centers already account for around 4 percent of electricity demand, with projections rising to as much as 9 percent by 2030.

This scale makes design decisions irreversible once construction begins.

Life Cycle Assessment addresses this problem directly. LCA evaluates impacts from cradle to grave, covering construction materials, site preparation, operational energy and water use, refrigerants, upgrades, and decommissioning. The methodology is governed by ISO 14040 and ISO 14044.

The European Commission’s International Reference Life Cycle Data System further standardizes data quality and comparability.

For practitioners, LCA enables direct comparison of design scenarios. These include evaporative versus closed-loop liquid cooling, air-cooled retrofits versus immersion-ready builds, and conventional concrete shells versus lower-carbon alternatives. U.S. Department of Energy research and government analyses indicate that selecting cooling technologies and strategies (such as air-cooled vs. water-cooled systems) significantly affects electricity demand and water consumption in infrastructure such as buildings and data centers. Modeling frameworks that account for local climate conditions, load profiles, and cooling system types show that these choices can result in materially different electricity and water use outcomes, with variability that can reach double-digit percentages under certain climate and load conditions.

Most importantly, LCA quantifies trade-offs. When reducing water consumption increases electricity demand, or when efficiency gains raise embodied carbon, LCA shows the net outcome. This approach allows companies to demonstrate why a specific configuration represents the least-impact, most resilient option before impacts are locked in.

Eco-Design Is Architecture for Real-World Constraints

Eco-design is not a set of add-ons. At the data center scale, it is an infrastructure architecture under constraint.

It begins with site selection grounded in grid and water reality. This means choosing locations with documented grid expansion capacity and integrating basin stress, water quality, and long-term pricing into siting decisions.

It continues with modular, right-sized build-outs. Oversizing capacity locks communities into unnecessary peak loads. The U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) reports that its High-Performance Computing Data Center has achieved exceptionally low power usage effectiveness (PUE), with an annualized average around 1.036 through efficient cooling, warm-water liquid cooling, and waste heat reuse. In addition, NREL documented significant improvements in water-use effectiveness (WUE) by installing a thermosyphon-cooler hybrid system that reduced on-site cooling water consumption by about half, without negatively impacting energy efficiency.

Cooling design is no longer an optional engineering detail. AI racks increasingly exceed the limits of air cooling. Direct-to-chip liquid cooling, rear-door heat exchangers, and immersion systems significantly reduce fan energy and, in closed-loop configurations, limit evaporative water demand.

Waste heat recovery further differentiates viable infrastructure. In Finland, Microsoft’s collaboration with Fortum — through Microsoft’s new data center facilities in Espoo and Kirkkonummi — is expected to supply approximately 40 % of the district heating demand for Fortum’s customers in the Espoo–Kirkkonummi–Kauniainen part of the Helsinki region once fully operational by recycling waste heat from the data centers into the local district heating network.

These outcomes are only achievable when eco-design is embedded at the planning stage rather than added after opposition emerges.

Why Paying More Cannot Be the Default Model

Microsoft’s cost-absorption approach addresses immediate friction points. It does not scale as a long-term growth model.

As AI infrastructure expands into regions with constrained grids, volatile power markets, and tightening water regulation, post-hoc compensation becomes inefficient. Governments have made clear that AI capacity will be supported, but cost shifting and open-ended subsidies will not.

LCA-driven eco-design offers a different proposition. It allows companies to demonstrate responsibility through design rather than remediation.

What the Next 24 Months Will Reward

Projects that succeed will plan like utilities, not just developers. Grid operators are already warning that AI-driven load growth is reshaping regional demand curves.

Cooling architectures that reduce both electricity and water demand will become baseline expectations for AI facilities rather than premium options.

Community acceptance will increasingly depend on formalized benefit agreements that codify power cost neutrality, water replenishment, and workforce investment. Microsoft’s recent framework is accelerating this shift.

Final Perspective

Algorithms may operate in the cloud. Infrastructure operates within physical limits.

When ISO-aligned Life Cycle Assessment and eco-design guide site selection, cooling strategy, grid integration, water sourcing, and heat recovery from the start, AI infrastructure becomes defensible to regulators and viable for communities.

That is what will distinguish deployable AI infrastructure from projects that never break ground.

Talk to One of Our Experts

Get in touch today to find out about how Evalueserve can help you improve your processes, making you better, faster and more efficient.