Context – a world in urgent need of solutions to the plastic crisis

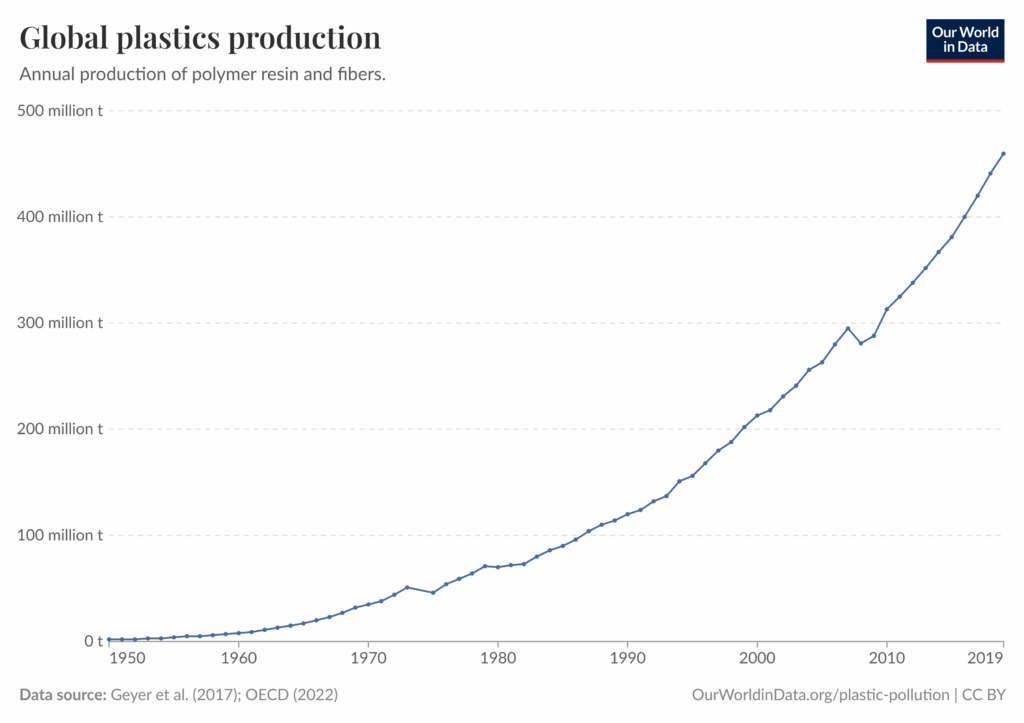

Plastic production has grown dramatically in recent decades. Each year, more than 450 million metric tons of plastic waste are generated, much of which is used in packaging that is discarded after a single use.

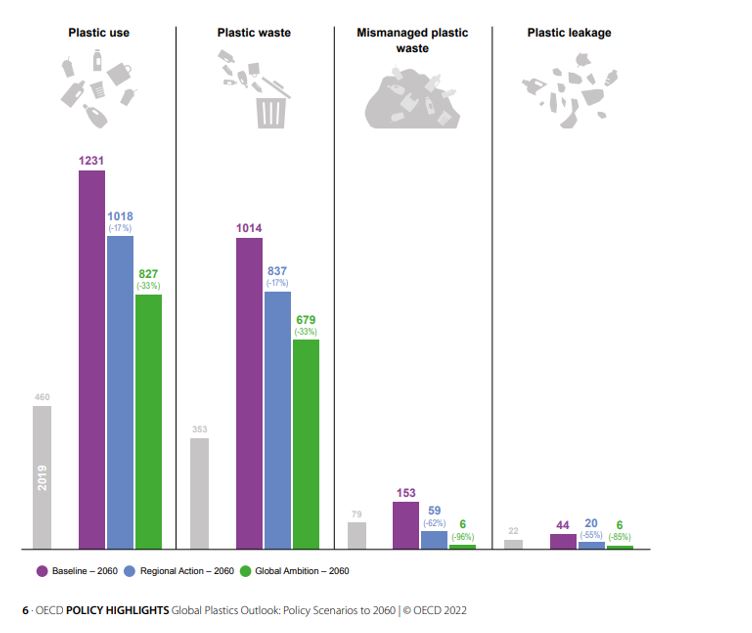

The OECD warns that the amount of plastic waste produced globally is on track to almost triple by 2060, with around half ending up in landfill and less than a fifth recycled. Models in the OECD’s Global Plastics Outlook project suggest that global plastics consumption could rise from 460 million tonnes (Mt) in 2019 to 1,231 Mt in 2060 without bold policy measures. Plastic leakage into the environment is expected to double to 44 million tons per year, while the build-up of plastics in rivers and oceans could more than triple, from 353 million tons in 2019 to 1,014 million tons in 2060.

Plastic pollution is not only an environmental issue, but also a substantial economic burden. About 95% of plastic packaging is discarded after a single use, representing a staggering loss of monetary value of up to US$120 billion annually. Developed countries consume up to 20 times more plastic per capita than developing nations, and plastic now accounts for at least 85 % of marine litter. Oceans, rivers, and lakes currently receive plastic waste equivalent to more than 2,000 garbage trucks’ worth of waste every day. Plastics production also contributes significantly to climate emissions: the petrochemical industry utilizes approximately 14% of the world’s petroleum and 8% of its natural gas, with around 9 million barrels of oil consumed daily to produce plastic.

Despite growing recycling efforts, less than 9% of collected plastic waste is effectively recycled; the rest is sent to landfills, burned, or leaks into the environment. At current recycling rates, the growth in plastic production will outpace recycling capacity, and more than 60% of plastic’s emissions occur during the production of pellets. These figures underscore the need for upstream innovation that reduces dependence on fossil-based plastics, as well as downstream innovation that improves recycling and reuse.

These figures underscore why the plastic problem is more than just an environmental issue — it is also an economic and systemic concern. To understand why innovation is so vital, we must first clarify the core challenge that it addresses.

The challenge – overproduction and waste mismanagement

A twofold challenge defines the global plastic crisis:

- The sheer volume of plastic being produced — much of it derived from fossil fuels and used for single-use purposes — is unsustainable. Demand is rising faster than capacity to recycle or replace it, embedding emissions and waste into the global economy.

- Inefficient waste management. Less than 9% of collected plastic waste is effectively recycled. The majority is burned, landfilled, or leaks into the environment. At current rates, recycling cannot keep pace with the growth in production.

This dual challenge means that recycling efforts alone cannot solve the problem. What is needed is innovation at both ends of the spectrum: upstream solutions to reduce plastic dependence at the source, and downstream solutions to better manage the plastics already in circulation.

With the challenge defined, the question becomes: who is bringing together the stakeholders to enable such systemic change? This is where the Global Plastic Action Partnership comes into play.

The role of the Global Plastic Action Partnership (GPAP)

In 2025, the Global Plastic Action Partnership (GPAP) – the World Economic Forum’s platform for accelerating national solutions to plastic pollution – hit a significant milestone. The programme had set itself the goal of forming 25 National Plastic Action Partnerships (NPAPs) by 2025. New members joining the network in late 2024 and early 2025 included Angola, Gabon, Guatemala, Kenya, Senegal, Tanzania, and Bangladesh. This expansion makes GPAP the world’s largest initiative tackling plastic pollution; the network now covers 25 countries and the state of Maharashtra, India, reaching more than 1.5 billion people. GPAP’s NPAP model works by bringing together policymakers, business leaders, and civil‑society organisations at the national level to agree on a shared roadmap for reducing plastic waste.

Beyond producing reports, GPAP creates national plastic action platforms, convenes communities, and curates conversations. It brings together policymakers, businesses, civil society advocates, and entrepreneurs to align on common approaches for addressing plastic. GPAP is also building an electronic knowledge toolkit to help countries replicate national strategies and is connecting game-changing, locally driven innovations with resources so that solutions can move from incubation to. These platforms offer opportunities for innovators to share intellectual property (IP) strategies and explore collaborative licensing or open‑innovation models. IP plays a crucial role in this context, as it not only protects the rights of innovators but also fosters collaboration by providing a framework for sharing and licensing innovative solutions. By encouraging the sharing of IP strategies, GPAP is promoting a culture of collaboration and innovation in the plastic sustainability sector.

Here, innovation intersects directly with intellectual property (IP). Patents and licensing frameworks can transform good ideas into investable ventures, while collaborative IP strategies enable solutions to spread more quickly across markets. GPAP, by fostering collaboration, is positioning IP as a lever for scaling solutions to the plastic crisis.

Innovation & IP trends – upstream and downstream solutions

Patents require inventors to disclose the underlying technology well before products reach the market, often by several years. This makes patent data a uniquely forward-looking source of intelligence, offering a clear view into corporate R&D pipelines and future technologies. Because these disclosures are standardized and publicly available, metrics derived from patent data provide objective insights into innovation activities across industries. At a global scale, they also highlight emerging technology trends and reveal how companies are channeling investment into inventions related to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Upstream innovations: new materials and product redesign

Innovation in plastic technology has more than tripled since 2015. According to a report by GovGrant published in 2023, the total number of global patent filings relating to plastic alternatives rose from approximately 605 in 2015 to about 1,840 in 202. Many of these inventions focus on new materials and product redesign, such as biodegradable compositions made from biopolymers or recycled plastic, improved plastic products that are easier to recycle, and packaging that uses less material. The European Patent Office analysed global patent activity. It concluded that the United States and Europe are leading innovators, accounting for two-thirds of international patent filings related to circular plastics between 2010 and 2019.

Bioplastics and natural polymers. Examples such as Lactips, a French start-up founded in 2014 (based on casein research initiated in 2007–2008), have developed patented technology to turn the milk protein casein into thermoplastic, biodegradable, and water-soluble pellets suitable for industrial molding—without requiring changes to existing plastic-processing equipment. Their innovation enables the production of plastic films, injection-molded parts, or coatings that dissolve entirely in water or biodegrade without releasing microplastics. Its product is biodegradable in all environments and does not fall under the European Union’s REACH or single-use plastics directives because it is 100 % natural. IP protection has enabled Lactips to attract investment and scale up production: the company operates a 4,200 m² plant and a large R&D centre with a team of 50 people. Similarly, Notpla, a London-based UK start-up co-founded by Pierre‑Yves Paslier and Rodrigo García Gonzalez, holds patents covering its seaweed-derived encapsulating method and biodegradable coating, which underlie its Ooho edible‑water bubble and “Notpla Coating” technologies. In 2022, Notpla won the Earthshot Prize in the “Build a Waste‑Free World” category—an accolade that significantly boosted its investment, visibility, and scale-up of truly compostable packaging solutions.

Composite and recyclable materials. Innovators are exploring electrochemical conversion of captured carbon dioxide to ethylene (a key ingredient in plastic bottle caps) and designing packaging using vacuum packing or resealable packs to reduce material consumption. Improvements in product design include removing coloured dyes and sleeves from bottles to enhance recyclability. Many of these inventions are patented, enabling companies to recoup R&D costs and share technology via licensing.

The logic is straightforward: upstream innovation tackles the challenge of overproduction by replacing fossil-based plastics with viable, scalable alternatives — and IP makes this transformation commercially viable.

Downstream innovations: recycling, sorting, and circular systems

Downstream innovations aim to close the loop through better recovery and recycling technologies. According to the patent analysis, innovations fall into two main downstream categories: novel processes and machinery for recovering, separating, and recycling plastic waste, as well as software-driven systems that track the life cycles of plastic products. For example:

- Advanced recycling technologies. Mura Technology’s Hydro‑PRS™ (Hydrothermal Plastic Recycling System) / Hydro‑PRT® (Hydrothermal Plastic Recycling Technology) is an advanced, hydrothermal recycling process that employs supercritical water—water at elevated temperature and pressure—to “cut” long-chain plastic polymers into shorter‑chain hydrocarbons. These recycled hydrocarbons (e.g., naphtha, gas oils, heavy wax) serve as circular feedstocks for producing virgin-grade plastics and other materials such as road asphalt additives. Their patents have attracted considerable attention, with third-party observations filed against some applications, highlighting the competitive value of IP in this field. Another innovation is plastic-to-monomer recycling, which also involves the use of patented catalysts and process designs.

- Sorting and digital identification. Sorting and separating plastic waste is highly innovation-intensive. Reath Technology offers a “Digital Passport” software solution based on the reuse.id open Data Standard—a system that assigns each reusable item of packaging (e.g., pouches, containers) a unique digital identifier and captures its lifecycle journey (‘stamps’) through scans. This enables brands to track and trace each reusable asset across production, filling, consumer use, and return, while generating insights for logistics, sustainability, and regulatory compliance. The system relies on software, which is protected by copyright and, where it produces a technical effect, may be patentable. Digital passports help track contamination and enable extended producer responsibility (EPR) schemes.

- Data and behavioural insights. Innovators are using data analytics to optimise collection routes and design consumer feedback loops. GPAP emphasizes behavior change as one of its key pillars and works with partners to catalyze coordinated action.

Here, innovation is crucial because current recycling systems are insufficiently efficient to handle the increasing volumes of waste. Downstream patents ensure new recovery technologies are competitive, investable, and scalable, making them indispensable to solving the second half of the plastic challenge: waste management.

Conclusion

The global plastic crisis presents a clear challenge: too much plastic is produced, too little is recycled, and too many emissions are embedded in the process. Left unchecked, plastic waste could almost triple by 2060, overwhelming ecosystems and economies alike.

Innovation is the essential lever for change. Upstream, patents support the development of bioplastics, natural polymers, and more innovative designs that cut plastic use at its source. Downstream, IP enables advanced recycling, digital traceability, and data-driven circular systems that keep plastics in productive use.

In short, without innovation, the plastic problem will only grow. With innovation — and IP to support investment, licensing, and scaling — solutions can move beyond the lab and into global markets. Platforms like GPAP illustrate how coordinated action can align these efforts, ensuring today’s inventions become tomorrow’s standard practices.

To overcome plastic pollution, we must recognise that the challenge is systemic, but also solvable. IP-savvy innovation is indispensable — and in our next blog, we’ll delve further, examining how corporations and policymakers are utilizing patents, licensing frameworks, and regulatory levers to shape the future of plastics.

Talk to One of Our Experts

Get in touch today to find out about how Evalueserve can help you improve your processes, making you better, faster and more efficient.